Reports

Report title

Lead author: Caroline Wang, China Analyst, CEF (caroline@climateenergyfinance.org)

Tim Buckley, Director, CEF (tim@climateenergyfinance.org)

Contributing editor: AM Jonson, Editorial Director, CEF (annemarie@climateenergyfinance.org)

xx October 2025

Author profiles

LEAD AUTHOR: Caroline Wang, China Analyst, CEF

Caroline is passionate about empowering understanding, exchange and collaboration between Australia and China to accelerate decarbonisation and deliver mutual economic benefits. She has a decade’s experience in law, policy and international relations across Australian public administration and overseas. A passionate interculturalist, Caroline is fluent in English, Chinese, French and Italian. Prior to joining CEF, she was a Senior Policy Advisor at NSW Premier’s Department where she facilitated the first ever knowledge-sharing collaboration between the NSW Government and the UN Office for Disaster Risk Reduction. She has written many government and parliamentary research and policy papers, including the report of the Australian Senate Inquiry into the 2019-20 bushfires. Caroline has led in strengthening international partnerships across national defence, education and diplomacy, including preparing multiple policy briefings and research papers to support executives’ and ministers’ international engagements.

Tim Buckley, Founder and Director, CEF

Tim Buckley has 35 years of financial market experience covering the Australian, Asian and global equity markets from both a buy and sell side perspective. Before starting CEF as a public interest thinktank in 2022, Tim founded the Australia and Asian arms of the global Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis in 2013 and was Australasian Director until 2022. Prior to this, Tim was a top-rated equity research analyst over 2 decades, including as head of equity research in Singapore at Deutsche Bank; MD and head of equity research at Citigroup for 17 years; and head of institutional equities at Shaw & Partners. From 2010-2013, Tim was co-MD of Arkx Investment Management, a global listed clean energy investment start-up jointly owned with Westpac Bank. Tim is widely recognised and extensively published as an expert on Australian and international energy transition and the accelerating shift of global capital to decarbonisation, and is a sought after commentator and advisor.

Dr. Annemarie Jonson is Editorial Director, CEF.

Established in 2022, Climate Energy Finance (CEF) is an Australian based, philanthropically funded think tank. We work pro-bono in the public interest on mobilising capital at the scale needed to accelerate decarbonisation consistent with climate science. Our analyses focus on global financial issues related to the energy transition, and the implications for the Australian economy, with a key focus on threats and opportunities for Australian investments and exports. Beyond Australia, CEF’s geographic focus is the greater Asian region as the priority destination for Australian exports. CEF also examines convergence of technology trends in power, transport, mining and industry in accelerating decarbonisation. CEF is independent, non-partisan and works with partners in NGO, finance, business, research, and government.

Contact: caroline@climateenergyfinance.org | tim@climateenergyfinance.org | annemarie@climateenergyfinance.org

We pay our respects to the Traditional Owners of the unceded lands on which we live and work.

© Climate Energy Finance 2025. All material in this work is copyright Climate Energy Finance except where a third party source is indicated. CEF copyright material is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia License. You are free to copy, communicate and adapt the material with attribution to CEF and the authors.

IMPORTANT: This report is for information and educational purposes only. CEF does not provide tax, legal, investment or accounting advice. This report is not intended to provide, and should not be relied on for, tax, legal, investment or accounting advice. Nothing in this report is intended as investment advice, an offer or solicitation of an offer to buy or sell, or a recommendation, endorsement, or sponsorship of any security, company, or fund. CEF is not responsible for any investment decision made by you. You are responsible for your own investment research and investment decisions. This report is not meant as a general guide to investing, nor as a source of any specific investment recommendation. Unless attributed to others, any opinions expressed are our current opinions only. Certain information presented may have been provided by third parties. CEF believes that such third party information is reliable, and has checked public records to verify it wherever possible, but does not guarantee its accuracy, timeliness or completeness. It is subject to change without notice.

Contents

Foreword

TBC…

Executive Summary

Green industrial partnerships with Chinese clean tech signal a new era of South-South cooperation

The past three years have seen an extraordinary surge in outbound direct investment (ODI) by Chinese clean tech manufacturers and renewable energy companies, driving a rapid acceleration of the global green-industrial transformation.

Since CEF’s “Green Capital Tsunami” October 2024 report, our updated tracking reveals that Chinese firms have pledged an estimated US$35 billion in new overseas renewable energy infrastructure and manufacturing projects across batteries, battery materials, solar PV, wind, EVs and green hydrogen (see tables on pages xx and xx) in countries as diverse as Vietnam, Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand, Turkiye, Brazil, Hungary, Spain, France, Portugal, Azerbaijan, Zambia, Egypt, Morocco, Oman and Saudi Arabia. This builds on the $100bn committed since 2023 that we had identified in our October 2024 report.

This is part of a broader wave that, since 2022, has mobilised over US$250 billion of private Chinese capital across 54 countries.11. Net Zero Industrial Policy Lab, China’s Green Leap Outward: The rapid scale- up of overseas Chinese clean-tech manufacturing investments, 9 September 2025..

The sheer scale and depth of Chinese clean tech firms’ “going global” push over the last three years are bringing about a dramatic shift in the global energy and economic landscape towards a China-centric supply chain configuration. Donald Trump’s re-election which has seen the US’ withdrawal from the Paris Agreement and the One Big Beautiful Bill have further enhanced China’s clean tech industrial and innovation leadership, while tariffs have failed to slow down Chinese clean tech exports which have continuously found demand in other markets.

In an era of rising protectionism, the trend of the shift from “product export” to “industry export” and market diversification reflects strategic adaptation by Chinese clean tech firms in a changing global environment. Push and pull factors are influencing this trend – from fierce price wars at home, to rising geopolitical risks, and import tariffs. The win-win of investment and technology cooperation in green manufacturing facilities and clean energy infrastructure stems from alignment with host countries’ net zero targets and green industrialisation priorities with a focus on building domestic capabilities through learning and technology transfer. This is exemplified in the EV battery value chain, with 7 of the top 10 global battery manufacturers being Chinese multinationals, led by CATL with 40% market share.22 CNEVPost, Global EV battery market share in 2024: CATL 37.9%, BYD 17.2%, 11 February 2025.

Since Oct 2024, China added $35bn to its clean-tech ODI, with the following emerging trends:

- Localised, partnership-based projects: Nearly every large-scale China ODI project is structured as a JV with local or state-linked partners to navigate local content rules and industrial-policy incentives.

- Technology transfer & R&D localisation: Many projects integrate R&D and training centres and recycling centres, signalling a deliberate shift from export-only manufacturing to embedded innovation ecosystems.

- Green diplomacy and South–South cooperation: Almost all of the projects are in the Global South or emerging markets, which includes most of the developing world. The surge in clean-tech manufacturing investment represents a substantial opportunity for Global South countries to host green ODI and enhance their participation in the global green technology market. Several announcements coincided with high-level state visits, underscoring clean-energy ODI as a diplomatic instrument of green energy statecraft.

Across the world, policy approaches to clean-tech industrialisation are diverging.

Advanced economies — notably the United States and Europe — are tightening trade, technology, and subsidy regimes to manage strategic dependencies and protect domestic industries. Meanwhile, many emerging economies are moving in the opposite direction, liberalising investment conditions and offering fiscal incentives such as tax breaks, concessional land and joint-venture facilitation to build production capabilities and access technology.

The divergence is as pronounced in evolving global trade dynamics – China now exports over 50% more to the Global South ($US1.6 trillion) than to the US and Western Europe combined ($US1 trillion). A clear example is seen in the case of solar panels which saw global exports triple in five years – in 2024, exports to the Global South overtook the Global north, after more than doubling in 2 years.

Overseas investments in emerging markets are likely to continue in the age of tariffs, as Chinese firms pursue new growth opportunities and seek to reduce their reliance on OECD markets. Just in the first half of 2025, newly announced clean tech manufacturing deals with Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) partner countries reached a record $US23.2 billion, more than doubling compared to the same period last year. As they continue to head to the Global South, “the result could be a new order of global commerce where South–South trade becomes the new centre of gravity and Chinese multinationals emerge as the new key players”.

China’s ascent as a renewable energy superpower is also seen by many emerging economies as a valuable reference point, as its model demonstrates that decarbonisation and development can go hand in hand. Human capital being at the core of industrialisation, the proliferation of joint R&D centres and training programs – such as the China-Morocco Joint Laboratory for Green Energy and Advanced Materials, or the Thai-Chinese Dual Degree in New Energy Automotive Technology – demonstrate the role of collaborative training partnerships in skilling the local workforce in critical STEM fields required to enable the development of green industries.

Executive Summary for Australian policymakers

While China scales and partners globally, Australia has sought to pursue its Future Made in Australia agenda excluding partnership with Chinese supply chains.

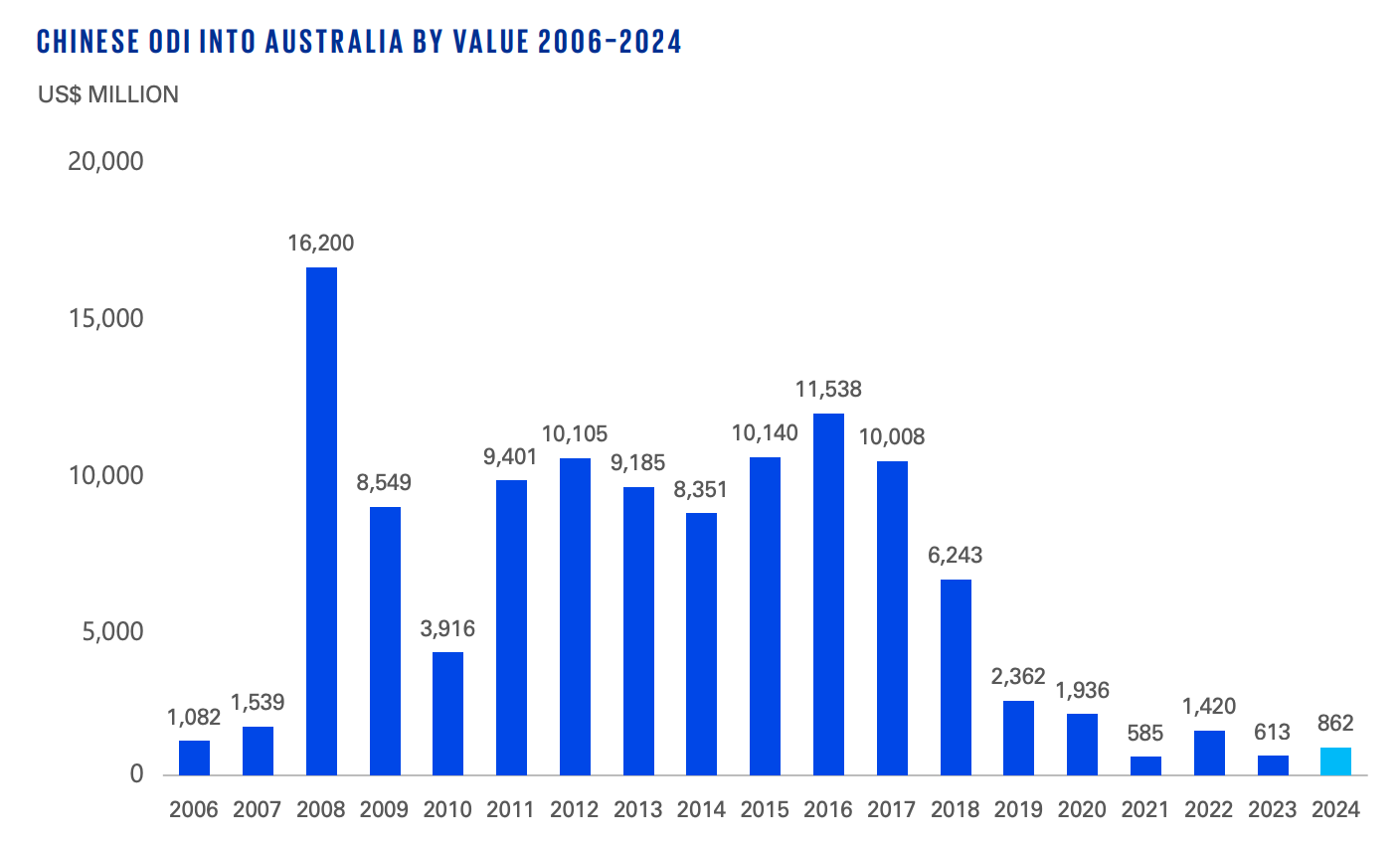

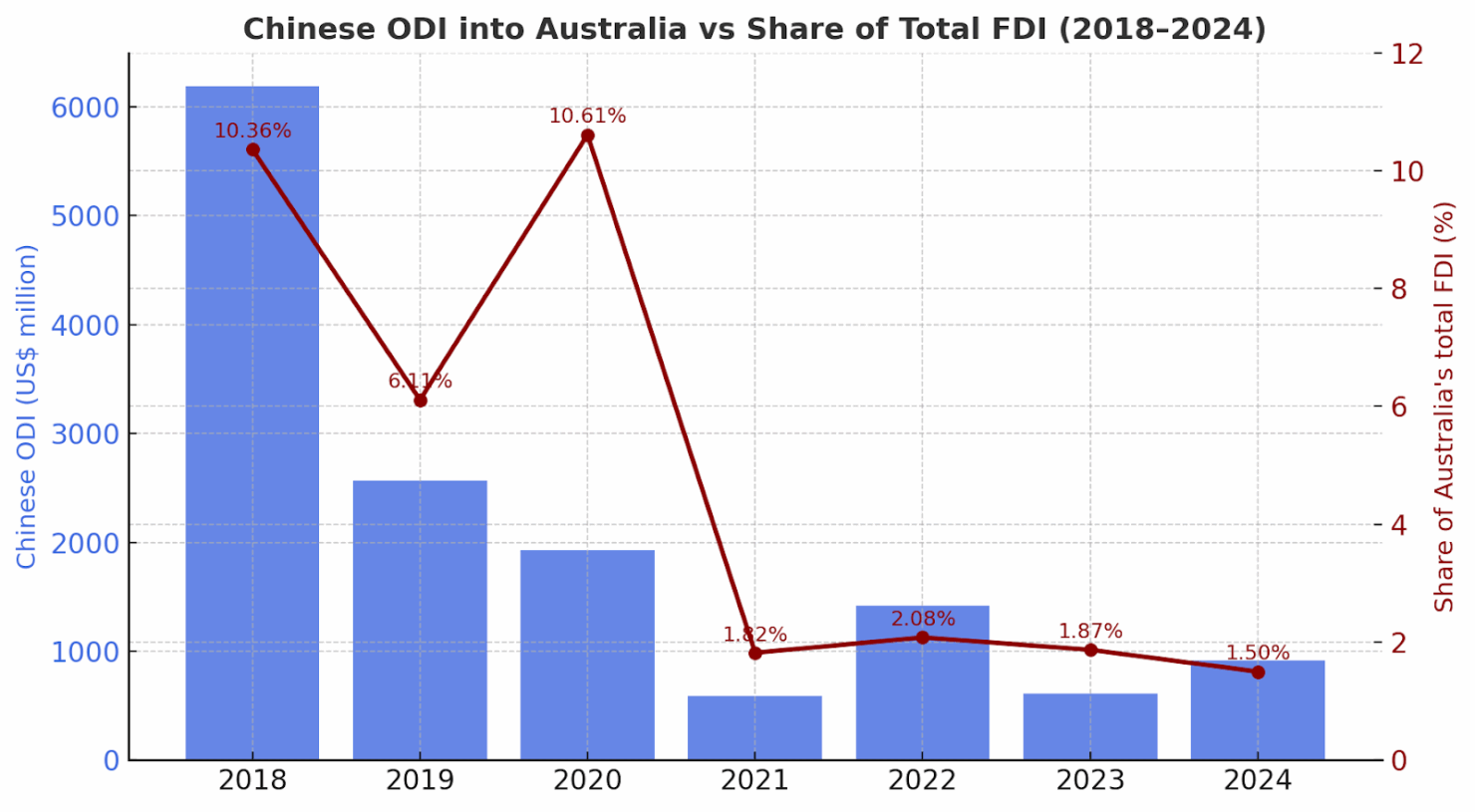

Chinese ODI into Australia has collapsed by 85% since 2018 when bilateral relations deteriorated sharply under the Morrison Government, now making up only 1.5% of the total ODI from all countries investing here, a decline from the already exceptionally weak 1.87% in 2024. 2024 recorded the third lowest value and number of transactions since 2006 at just US$882m, a tiny fraction of the peak of US$16bn in 2008 and US$11bn in 2016.

Although Australia-China relations have gradually thawed thanks to stabilisation efforts made by the Albanese Government, including the Prime Minister’s July 2025 visit to China, risk-driven caution continues to define the Australian federal government’s approach to China, maintaining a chilling effect on two-way business and research engagement.

While Australia’s clean-energy ambition is widely recognised, its execution capacity remains constrained by structural deficits across capital and capability, undermining the credibility of Australia’s net zero plan and ability to compete in the global clean-industry race.

As we seek to illuminate in this report, the Australian federal government approach of excluding partnership with Chinese firms for geopolitical reasons, leads to trade-offs that undermine Australia’s ability to meet the core objectives of Future Made in Australia (FMIA) and the Net Zero Plan, designed to diversify and decarbonise the country’s economy.

Australia’s small domestic market, low industrial base, and lack of clean energy skilled workforce, means that collaboration with global supply chain and technology leaders is not an option if the country’s leaders are serious about achieving FMIA. Whether it’s critical minerals processing, solar PV or battery manufacturing, Chinese firms control not only these supply chains, but critically, hold world-class industrial and technology expertise in green industries.

As many other countries with serious industrialisation ambitions are showing, using green energy statecraft to attract strategic ODI and technology partnerships with world-leading firms in areas of comparative advantage (e.g. EV value chain in Europe; solar manufacturing in the Middle East) is proving to be an efficient approach: learning by smart partnering such as through joint ventures, and integrating into existing supply chains. “As nations from Brazil to Spain reposition themselves through active partnership with Chinese clean-tech leaders, Australia stands as an outlier—treating opportunity as risk and falling behind the new industrial geography of the net-zero race.”

Finally, national competitiveness and industrial productivity require fundamentals including a skilled workforce, cheap and abundant electricity, and adequate infrastructure. Chief among these is access to low-cost, reliable clean power—without which manufacturing and value-added industries cannot thrive or attract investment at scale.

Under AEMO’s step change scenario, the NEM will need to triple grid-scale variable renewable energy by 2030, and increase it six-fold by 2050. Around 70% of capital invested in Australian renewable energy projects comes from foreign investors. Yet, Australia is becoming an increasingly less competitive environment for investment, according to a recent survey, due to lengthy and uncertain permitting processes, and grid connection bottlenecks. In July 2025, Professor Ross Garnaut AC called out chronic underinvestment in grid-scale solar and wind.

In short, Australia cannot meet its clean-energy and industrial-policy ambitions without faster renewable build-out, deeper global partnerships, and greater investment certainty. Addressing these structural deficits requires policy settings that are pragmatic, coordinated and internationally connected.

Recommendations for Australian policymakers

Grounding Ambition in Economic Realism

Australia’s ambition to build domestic clean-tech manufacturing capacity under the Future Made in Australia (FMIA) agenda must be grounded in commercial reality. Programs such as the Solar SunShot Program and Battery Breakthrough Initiative aim to enhance supply-chain resilience through domestic re-localisation. However, cost and scale dynamics in global clean-tech industries make it challenging for Australia to compete directly across all stages of these mature value chains.

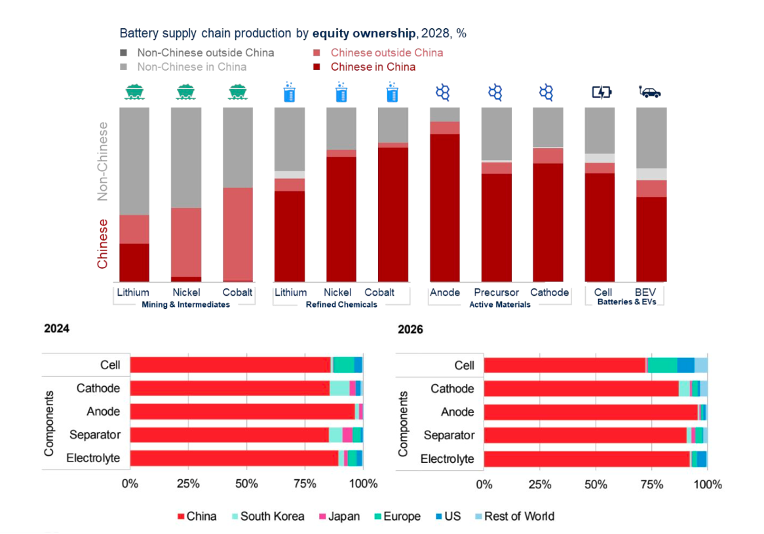

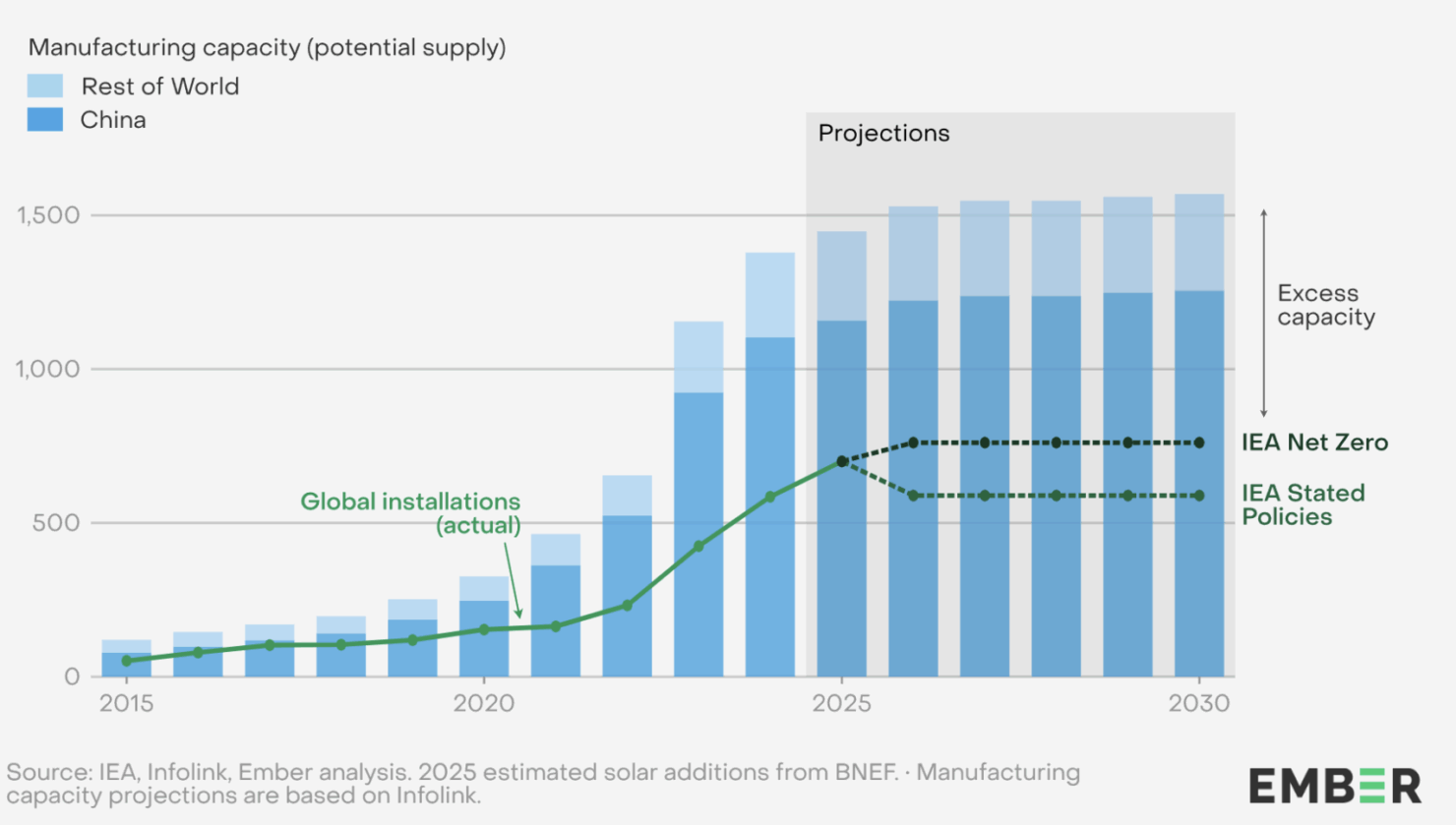

China currently accounts for 80–95 per cent of global production across solar and battery supply chains, underpinned by established industrial clusters, skilled workforces, and low-cost renewable power (see Figures X and Y). Australia’s comparative advantage lies not in replication but in strategic integration — targeting high-value segments of global supply chains where local strengths in resources, innovation, and governance can create durable value.

From Fragmentation to Coherence: Building an Integrated Net Zero Economic Strategy

Australia’s suite of federal net zero and related policies and programs —the Net Zero Plan, Future Made in Australia (FMIA), National Battery Strategy, Critical Minerals Strategy 2023-30, National Hydrogen Strategy 2024, AEMO Integrated Step Plan, jobs and productivity agendas, National Climate Resilience and Adaptation Strategy — pursue the cross-cutting objectives of decarbonisation, industrialisation, productivity, climate adaptation, and regional renewal.

Yet they currently operate in silos spread across 7 federal agencies, with fragmented responsibilities across agencies and little coordination amongst each other, let alone with state and territory agencies and local councils. This disjointed approach and lack of unifying mission substantially diminish the likelihood of achieving a successful energy transition and related objectives.

To rectify this, Australian Governments should adopt a form of ‘Green Energy Statecraft’ as put forward by UNSW Professor Elizabeth Thurbon, – an integrated, mission-led framework for governing the green transition – guided by three core principles: clarity, simplicity, and speed, underpinned by strong narrative leadership.

International experience—from Brazil, Spain, Hungary, and Saudi Arabia—demonstrates that coherent, whole-of-system governance delivers far greater industrial and climate outcomes than fragmented, program-by-program approaches.

Operational Priorities

1. Integrate and Simplify Governance

- Establish a National Industrial Transition Council, chaired by the Prime Minister, to align Net Zero, FMIA, and productivity objectives and coordinate delivery across portfolios.

- Unify investment and industrial-policy governance through clear mandates linking emissions reduction, regional development, skills, and supply-chain localisation.

- Streamline approvals via a single-window process for clean-tech project assessment across federal and state levels—cutting duplication and administrative delay.

2. Focus on Competitive Niches

- Concentrate support on sectors of comparative advantage—critical-minerals processing, electrolyser and storage innovation, grid integration, and recycling—rather than full solar or battery replication.

- Develop template investment and licensing agreements to ensure consistent, low-bureaucracy treatment for strategic projects.

- Introduce a “fast-track low-risk” approval stream for commercially viable proposals meeting climate and productivity objectives, with target decision times under 90 days.

3. Embed Economic Realism in Industrial-Policy Design

- Require rigorous cost–benefit and feasibility assessments for all FMIA-funded manufacturing proposals, benchmarked internationally.

- Commission independent analysis by the Productivity Commission to evaluate competitiveness and public-value creation.

- Replace open-ended subsidies with performance-based incentives tied to technology transfer, workforce training, and export potential.

4. Build and implement a Team Australia FMIA Partnership Strategy

- Establish Invest Australia, with an outward-facing and proactive mandate, to lead a whole-of-government, coordinated inward investment and technology-partnership promotion agenda aligned with FMIA and Net Zero priorities, as a one-stop shop for investors—removing duplication between Treasury, FIRB, Industry, and state agencies.

- Support the development of joint R&D and skills partnerships between Australian STEM faculties and vocational education institutes and leading Chinese training centres to accelerate capability building.

- Explore an Australia–China Green Industrial Cooperation Framework to facilitate collaboration in non-sensitive areas such as solar, battery, and critical-minerals value chains, and foster research partnerships between UNSW, ANU, CSIRO, and Chinese counterparts.

Implementation Principles

All programs under the FMIA and Net Zero Plan should adhere to three operational tests:

- Clarity – explicit mandates, transparent criteria, single-point accountability.

- Simplicity – streamlined procedures, standardised templates, minimal administrative layers.

- Speed – predictable timelines matching international norms for investment and project delivery.

SECTION 1:

The Rise of the Electrostate — China as the Engine of Global Decarbonisation

Over the past decade, China has consolidated its position as the engine of the global clean energy transition—what analysts now describe as the world’s first major “electro-state.” This has resulted from consistent government policies and massive investment favouring the rapid expansion of domestic renewable energy capacity such that in early 2025, combined wind and solar capacity overtook that of coal, marking a historic turning point in China’s energy system. According to latest analyses, China’s fossil fuel consumption is likely to begin falling soon under the twin trends of clean generation and end-use electrification

Driven by the government’s push to reduce China’s energy dependence on imported fossil fuels and its net zero goals, the effects have been dramatic for the country’s economy. Reduced energy costs, particularly through the exponential scaling-up of China’s solar photovoltaic industry, stimulated growth, jobs and created export markets.

In 2024, the so-called “new three” industries, namely, solar, electric vehicles (EVs) and batteries, contributed a record 10% to China’s GDP. China produced 93% of global polysilicon, 97% of solar wafers, 92% of battery cells, and 86% of solar panels (see Figures X and Y below) The rapid deployment of clean technologies has led to a decline in China’s carbon emissions for the first time, while their exports in 2024 alone are already shaving 1% off global emissions in the rest of the world.

Having successfully built a complete industrial supply chain for clean technologies at home which contributed a record 10% of China’s GDP in 2024 (equivalent to the total GDP of Australia), Chinese clean tech firms’ have shifted from “product export” to “industry export”. This reflects a necessary strategic choice, just as Japanese firms did in the 1980s–1990s and US firms in the 1950s–1970s.

Figure X: Chinaʼs Ownership Of The Battery Supply Chain

Figure Y: China’s projected solar manufacturing capacity outpaces even global net zero scenarios

Solar PV modules, GW

Source: Ember, China Energy Transition Review 2025

Global investment patterns

Chinese clean-tech firms, faced with weaker GDP growth, rising overcapacity, and fierce market competition at home, have been pushed to seek opportunities abroad, either through exports or outbound investment. Chinese-made solar panels, batteries, and EVs are accelerating electrification in developing economies, many of which are now leapfrogging the US in terms of electrification rates.

China’s dominance in electro-technologies—from power generation to grid infrastructure, storage, and mobility—is reshaping global energy and trade systems. Its rise as an “electrostate” marks not just a domestic transition but a profound shift in global economic and geopolitical dynamics. China’s clean-tech industrial dominance is becoming increasingly central to its national economic interest and soft power, especially in the Global South, as the world traverses a decade of instability and fracture.

Deepening cooperation with BRI partner countries has become Beijing’s strategic pillar for building its geopolitical influence in line with its consistent positioning as champion of the Global South to “better bridge the development gap between the North and the South”. China’s own green industrial transformation can offer lessons to other developing countries, including through its support for increased South-South cooperation.

As CEF covered in our Green Capital Tsunami report, China’s clean-tech outward investment since 2022 continues to trend in the Global South, which includes most of the developing world, in parallel with growing trade between China and the Global South. The surge in green manufacturing investment represents a substantial opportunity for Global South countries to host green FDI and enhance their participation in the global green technology market.

ASEAN continues to lead as the principal destination for new battery-materials and solar manufacturing projects, anchored by Indonesia, Thailand and Vietnam, where FDI openness and localisation requirements have successfully drawn in large-scale greenfield investments.

Europe rebounded strongly in 2024, recording €10 billion in new Chinese investment—up 47% year-on-year—dominated by greenfield EV and battery gigafactories in Hungary and Spain. In 2025, there has only been one new announced battery project in Europe, the €700 million Inobat battery gigafactory in Spain announced in September 2025.

The Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region has emerged as a global focal point for clean-energy industrialisation and investment partnership with China. Driven by national strategies that fuse energy transition, economic diversification, and industrial sovereignty, countries such as Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Egypt, and Morocco are building regional ecosystems that localise renewable-energy manufacturing, green-hydrogen production, and electric-mobility supply chains.

Latin America and Central Asia are also rising in importance as investors link critical-minerals extraction to local processing and renewable-generation projects, creating vertically integrated hubs in Brazil, Peru, Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan.

Meanwhile, Africa has seen record engagement, particularly in Kenya, Egypt and Zambia, where solar, wind and transmission projects are combining energy access with industrial upgrading.

As the Net Zero Industrial Policy Lab identified, the geographic distribution suggests that investment motivations can be categorized into three types: Seeking access to host countries markets, access to third-country markets, or access to raw material inputs.

By technology, battery-related investments dominate total value, driven by high-capex cathode, precursor and refining facilities. Europe continues to host most full-scale gigafactories, while the MENA region and ASEAN are attracting mid-stream components and precursor production. Solar manufacturing remains the second-largest category but is now far more geographically diversified, with module and glass plants proliferating in Europe, the Middle East and Southeast Asia. EV assembly and charging-infrastructure ventures have broadened China’s overseas footprint into mobility ecosystems, while early-stage hydrogen and ammonia projects signal the next frontier.

SECTION 2:

Global Context: The Rise of Green Energy Statecraft

The world is in the midst of a global ‘polycrisis’ – the term has been described as “when crises in multiple global systems become causally entangled in ways that significantly degrade humanity’s prospects. These interacting crises produce harms greater than the sum of those the crises would produce in isolation, were their host systems not so deeply interconnected.” In particular, climate change continues to intensify, and the latest studies have shown that limiting global warming to 1.5 degrees above pre-industrial levels is no longer possible.

This means traditional concepts of “national security” are no longer fit for purpose. Rather, a holistic approach to assessing and advancing the national interest is crucial because policymakers must grapple with pressing energy, economic, social, environmental and military security challenges simultaneously. This requires rethinking the relationship between the public and private sectors. That is, the public sector must take a leadership role.

This has been intensified in 2025 as the new US administration has leveraged its global prominence and historic position in launching a global trade war to try to entrench US-self interest. This is largely a reaction to the ongoing rise and rise of China’s economy as a global technology and manufacturing leader in many zero emissions growth industries of the future. We now live in a multipolar world, enabled by a progressive shift in economic weight to , where some 41% of world GDP in 2025 now comes from the BRICS – or the Global South, driven by sustained faster economic growth in many of these nations over the last two decades.

In the midst of the global race to net zero, we are seeing governments in developed and developing economies alike adopt an increasingly active and strategic role in guiding, shaping, and accelerating the green transition and reindustrialisation to advance a comprehensive national security-enhancing agenda.

Examples include:

- EU Clean Industrial Deal, which seeks to strengthen Europe’s net-zero manufacturing base, simplify permitting, mobilise public and private investment, and safeguard competitiveness through a framework of state-aid flexibility and the Net-Zero Industry Act.

- Spain’s new draft Law on Industry and Strategic Autonomy, which seeks “reindustrialisation to generate opportunities for social and territorial equity, to guarantee our strategic autonomy, attract industrial investment in Spain, promote innovation, competitiveness, the green transition, the decarbonisation of industry and its digital transition”.

- Brazil’s Nova Indústria Brasil, a new industrial policy that “places innovation and sustainability at the centre of economic development, encouraging research and technology in various different fields, alongside social and environmental responsibility”

- Hungary’s ‘150 new factories’ program with the framework of the New Economic Policy Action Plan to “ensure the recovery of the domestic industry and strengthen investment activity”

- Saudi Arabia’s National Industry Strategy as part of Vision 2030, focussed on “enhancing key industries while integrating cutting-edge technology and sustainability into its framework”

To illustrate this trend of rising state activism in driving green industrial transformation in the global net zero race, this report will highlight four case studies–Brazil, Spain, Hungary, and Saudi Arabia–which demonstrate the various tools and instruments of statecraft deployed to implement ambitious, indeed transformative, national economic and industrial agendas.

ODI remains the largest external source of industrial development finance. As part of the green energy statecraft toolkit, many governments have been actively courting Chinese clean-tech leaders to build local manufacturing facilities. The battery value chain dominated by Chinese multinationals like CATL and BYD has seen mega-deals arise in recent years. In Hungary, CATL is building a €7.3 billion battery gigafactory in Debrecen—Europe’s largest and the largest greenfield investment in Hungary’s history, while in Brazil, BYD’s US$1 billion electric-vehicle and battery complex in Bahia marks Latin America’s largest clean-tech investment.

And under Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030, Chinese firms such as TCL Zhonghuan and Jinko Solar are investing in large-scale wafer, cell and module plants to anchor a regional solar-manufacturing hub. These projects illustrate how governments are leveraging Chinese industrial capabilities to localise production and create jobs, reduce costs, and accelerate their energy transitions.

In contrast, the United States, under the new administration, has adopted a more defensive industrial and trade posture. Key provisions of the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) are being scaled back or suspended under the One Big Beautiful Bill, including tax credits and grant programs for renewable energy, EVs, and advanced manufacturing. This reversal has introduced policy uncertainty for clean-tech investors and accelerated efforts by global firms to diversify toward more predictable markets in Europe, Asia, and the Global South.

At the same time, Trump has set off a tariff rampage while intensifying investment-screening measures and restrictions related to “ownership and control of a project” by a “specified foreign entity” or a “foreign-influenced entity”.

The next section examines countries enacting green energy statecraft through strategic investment and technology partnerships with Chinese clean tech firms.

SECTION 3:

Green Energy Statecraft around the World

As defined by AsiaPacific4D, green energy statecraft refers to the strategic use of clean-energy policy, finance, technology, and diplomacy as instruments of national power and competitiveness. In an era when decarbonisation has become inseparable from economic, security and sustainability agendas, governments are deploying statecraft not only to meet climate targets, but to reshape global value chains, secure technological leadership, and anchor domestic reindustrialisation. This approach blends industrial policy with foreign and investment diplomacy—mobilising state-owned banks, strategic funds, and bilateral agreements to attract capital, localise manufacturing, and forge long-term supply partnerships.

The following country case studies illustrate this phenomenon in practice. From Spain’s legislative integration of reindustrialisation and ecological transition, to Hungary’s state-led facilitation of battery-sector investment, and Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030-driven diversification, Brazil’s developmental-diplomacy model, each represents a distinctive deployment of green energy statecraft reflecting local circumstances, capacities and priorities. It should be noted that there is no one-size-fits-all approach to GST in developing countries in light of their differing histories and endowments.

Yet, together they reveal how clean-energy industrialisation has become a core expression of national ambition—linking climate action, economic sovereignty, and geopolitical influence.

🇧🇷 Brazil — Developmental Statecraft for Green Industrialisation

Context & Drivers

Ecological Transformation and Industrial Renaissance

Under President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, Brazil has re-embraced an active developmental-state model, using industrial and foreign-policy instruments to drive a green reindustrialisation agenda. The twin policy pillars — Nova Indústria Brasil (NIB, 2024–2033) and the Ecological Transformation Plan (Plano de Transformação Ecológica)—link decarbonisation, technology localisation, and social inclusion as engines of national development.

NIB (2024–2033) mobilises R$300 billion (≈US$60 billion) in public and concessional finance through the National Development Bank (BNDES), the Financier of Studies and Projects (FINEP), and the Regional Development Fund (FDR),to reindustrialise Brazil via six priority missions, including 1) energy transition and decarbonisation; and 2) New mobility and digital transformation.

The Ecological Transformation Plan, led by the Ministry of Finance, provides a fiscal and regulatory platform to mobilise climate-aligned investment, reform credit markets, and integrate sustainability into industrial finance.

Recently, Lula’s government is also positioning Brazil, with its vast territory and mineral wealth, as a supplier of critical minerals to meet the global demand for clean technologies. In August 2025, Lula announced plans for a national strategic-minerals policy treating critical minerals as a matter of national sovereignty and committing to localising value-added processing before export.

Diplomatic Engagement and Strategic Partnerships

President Lula has placed economic diplomacy at the centre of Brazil’s reindustrialisation strategy, prioritising partnerships with China, the EU, and BRICS+ economies.

During his state visits to China (April 2023, November 2024, June 2025), Lula and President Xi Jinping signed more than 20 cooperation agreements in energy, green technology, agriculture, digital infrastructure, and industrial investment. These enhanced diplomatic efforts have contributed to a surge in Chinese FDI into Brazil—particularly in electric mobility, renewable energy, and critical minerals—reflecting deep alignment between the two nations’ industrial and climate priorities.

In a press conference following his engagements in China in May 2025, President Lula stated:

“Our relationship with China is very strategic. We want to learn and also attract more investment to Brazil. We want more railways, more subways, more technology. We want artificial intelligence. We want everything you can share with us. Because we need to learn to work together to achieve the results we need.”

Statecraft Tools

| Instrument / Tool | Description |

|---|---|

| New PAC 2023–26 Investment Program | Integration of industrial, energy, and climate goals through the Plano de Aceleração do Crescimento (New PAC 2023–26), an investment program coordinated by the federal government in partnership with the private sector, states, municipalities, and social movements to accelerate economic growth and social inclusion, generate jobs and income, and reduce social and regional inequalities. |

| Predictable Regulation | Streamlining of environmental-licensing procedures and digitalisation of federal permits under the Ministry of Environment and IBAMA to accelerate renewable and manufacturing projects. |

| Development Finance | Expansion of concessional lending via BNDES, FINEP, and the BRICS New Development Bank (NDB) for renewable-energy, hydrogen, and industrial projects. In 2024, BNDES allocated R$ 37 billion (≈ US$ 7 billion) to the energy-transition portfolio. |

| Strong diplomatic engagement with China through the lens of South–South Cooperation | Active leadership in BRICS+ green-energy initiatives; strengthened trade and investment ties through state visits to China (April 2023, November 2024, May 2025). Reactivation of the China–Brazil High-Level Coordination Commission (COSBAN) in 2023, chaired by Vice-President Geraldo Alckmin, to align investment cooperation under the BRI and NIB industrial priorities. |

Outcomes & Results

In 2024, despite global FDI contraction (–11% worldwide), Brazil’s inflows from China surged, representing 6% of China’s total outbound non-financial investment. Brazil was the emerging economy that attracted the most Chinese investment in 2024 and the third-largest destination of Chinese productive capital worldwide, behind the UK and Hungary. Chinese companies invested in 39 projects in Brazil—a historic record—with investments totalling US$4.18 billion, up 113% from 2023.

Sectoral breakdown (2024):

- Electricity & Renewables: 34% share (≈ US$1.43 billion) — solar, wind, and transmission lines.

- Manufacturing: record eight projects worth ≈ US$637 million, mainly EVs and batteries.

- Mining & Critical Minerals: surge in lithium and nickel exploration in Minas Gerais and Piauí.

BYD’s growth in Brazil has been staggering, with the recent launch of the Bahia factory, its largest EV plant outside Asia. Since entering the passenger vehicle market in 2022, the company has sold more than 170,000 electrified cars, including fully electric and plug-in hybrid models, and now dominates the electric segment with 74.4% of total sales. by 2027, 50% of the vehicle components will be domestic.

Image: President Lula and governor of Bahia, Jerônimo Rodrigues, pose with workers at the BYD electric vehicle plant in Bahia

Source: Joá Souza/GOVBA, 10 October 2025

| Project / Location | Chinese Partner | Investment (US$) | Policy alignment | Significance / Status |

| BYD Camaçari Complex (Bahia)Largest EV plant in South America; expected to generate≈ 20,000 jobs | BYD Auto | $978 million | NIB, 2024–2033 | Conversion of a former Ford plant into an EV and battery manufacturing hub. Production began July 2025; initial production volume is 150,000 cars per year, with the goal of reaching 300,000 in a second phase |

| Graça Aranha–Silvânia 1,500km Transmission Project≈ 30,000 jobs | State Grid Corp of China | $3 billion | NIB, 2024–2033 | One of Brazil’s largest infrastructure investments; construction of converter substation began June 2025; completion expected 2029 |

| Envision Energy sustainable aviation fuels production plant project | Envision Energy | $1 billion | Fuel of the Future Law (2024) establishes guidelines for the promotion of sustainable fuels, including green diesel, biomethane, and Sustainable Aviation Fuel (SAF). | Announced during Lula’s trip to China in May 2025 |

| Windey Energy Joint R&D Centre (Bahia) | Windey Energy Technology Group | Undisclosed | NIB, 2024–2033 | Announced during Lula’s June trip to China. Joint renewable energy R&D centre launched June 2025 |

Summary Insight: Brazil demonstrates how developmental diplomacy and green-industrial statecraft can converge to drive both economic diversification and climate ambition.

Through Nova Indústria Brasil and the Ecological Transformation Plan, the country is building an integrated clean-energy and manufacturing ecosystem supported by state finance, predictable regulation, and diversified foreign partnerships. While deepening engagement with China remains central to Brazil’s industrial renaissance, its emphasis on sovereignty, localisation, and multilateral balance distinguishes it as the leading Latin-American example of progressive green reindustrialisation.

🇪🇸 Spain — Strategic Autonomy through Partnership

Context & Drivers

Long-term national vision and policy stability

Spain’s Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez is currently in his third term and is the longest-serving Spanish Prime Minister since 2004. His seven-plus years of continuous leadership have given Spain exceptional political stability by EU standards, and this continuity has been underpinned by a long term national vision articulated under Spain 2050, and the sustained development and implementation of national policies such as the updated Integrated National Energy and Climate Plan 2023-30 focussed on strengthening energy independence, Spain’s Foreign Action Strategy 2025-2028 and the Industry and Strategic Autonomy Bill.

Spain has cast itself as an EU first-mover in the ecological transition and frames green industry as a pillar of national competitiveness and jobs, in line with EU policies and frameworks (Green Deal, REPowerEU, Net-Zero Industry Act), to crowd in investment and accelerate supply-chain localisation. Public messaging links this ambition directly to worsening climate risks (notably severe wildfire seasons).

Spain’s strategy couples industrial policy instruments (PERTE programs, especially PERTE VEC for EVs/batteries) with region-led attraction packages (e.g., Valencia, Aragón, Extremadura), and EU-compliant investment screening.

Spain’s navigation of US-China geostrategic competition and EU-China trade tensions

Amid ongoing EU-China trade tensions and broader geopolitical uncertainties, Spain’s strengthening diplomatic and economic ties with China reveals a delicate balancing act.

When a Senator from its Centre-Right Party asked the Government in a January 2025 Senate sitting how it plans to balance the need to attract foreign investment with the potential impact on diplomatic relations with the US and other strategic allies, noting CATL has been included on the “blacklist” of the United States Department of Defense, the Spanish Government responded:

“Spain maintains a balance between its relationship with China and its commitments to its Western allies. Spain is open to foreign investment and has an investment control mechanism that allows it to balance attracting investment with safeguarding our strategic interests.”

Spain’s balancing act also surfaced at the EU level: in October 2024, Madrid abstained from the vote to impose tariffs on Chinese EV imports. This came following a trip to China, when he publicly urged the EU to reconsider the tariffs, signalling a change in Spain’s previous position. This was in response to concerns that one of its biggest export sectors — pork — could be hurt by a Chinese anti-dumping probe launched after the EV tariff plan was announced.

Statecraft Tools

| Instrument / Tool | Description |

|---|---|

| Strategic Industrial Governance | Spain’s forthcoming Law on Industry and Strategic Autonomy seeks to modernise industrial governance to promote domestic manufacturing and high-value supply chains. It introduces clear approval procedures for “strategic projects,” streamlined permitting, and public–private co-financing facilities coordinated by the Ministries of Industry and Economy. |

| EU Alignment and PERTE Integration | National industrial programs are embedded in EU frameworks such as the Green Deal Industrial Plan, REPowerEU, and Net-Zero Industry Act. Within these, flagship initiatives like PERTE VEC (Electric Vehicle and Battery Value Chain) and PERTE Industrial Decarbonisation mobilise large-scale public and private investment, reinforcing supply-chain localisation and technological competitiveness. |

| Regional Coordination and Industrial Decentralisation | Autonomous regions—particularly Valencia, Aragón, and Extremadura—lead in project attraction through fiscal incentives, renewable-energy infrastructure, and industrial-park development. |

| Green Public Procurement | Announced by Prime Minister Sánchez in September 2025, Spain’s expanded green-procurement framework mandates that public-sector purchases prioritise low-carbon or zero-emission products and services. The measure positions the state as a major demand-driver for clean technologies. |

| Transparent Investment Screening | The Ministry of Industry, Commerce and Tourism administers EU-compliant, rules-based investment reviews distinguishing between strategic and non-sensitive sectors. |

| Diplomatic Activism to strengthen economic Partnership with China | Spain complements domestic policy with enhanced diplomatic engagement to attract high-value green investment. Prime Minister Sánchez has met with President Xi in China three times in two and a half years. Sánchez was also the first European leader to make an official visit to China following Trump’s announcement of universal tariffs. During that visit in April 2025, Sánchez met with representatives of a dozen major Chinese companies present in the Spanish market or considering investing there in the automotive, battery, and renewable energy sectors. |

Perception of investment environment by Chinese companies

Europe has one of the most open investment environments among developed economies. Chinese companies see Spain as an attractive environment for investment. According to a 2023 KPMG study on Chinese FDI in Spain, the top three reasons cited were: 1) geographic location; 2) size of the Spanish market (47 million population), and 3) its position in terms of access to other markets, serving as a platform for access to other markets in the European Union, North Africa, the Middle East, and Latin America.

The study also highlighted that “bilateral relations at the institutional level play a crucial role for Chinese companies, and they closely monitor the development of these relations between governments, as well as the level of acceptance and welcome of Chinese investment in the destination country.”

Outcomes & Results

In December 2024, Stellantis and CATL announced a 50:50 joint venture worth €4.1 billion in investment to build a lithium iron phosphate (LFP) battery plant in Zaragoza, a sum exceeding the total investment in any EU country in 2024. The facility, targeting an annual production capacity of 50 GWh, will be CATL’s third battery plant in Europe after Germany and Hungary.

Spain now hosts one of Europe’s most diversified battery-manufacturing pipelines—spanning global OEMs (Volkswagen, Stellantis), Chinese leaders (CATL, Envision AESC), and European innovators (InoBat, Basquevolt). Together these projects represent ≈ €11 billion in announced investment and over 10 000 direct jobs, positioning Spain as an emerging European hub for EV and battery production.

🇪🇸 Major Battery Manufacturing Projects Announced since October 2024

| Name / Location | Company / Partners | Investment (€) | Status (2025) |

|---|---|---|---|

| CATL–Stellantis LFP battery gigafactory — Zaragoza (Aragón) | CATL (China) + Stellantis (Europe) | 4.1billion, including €300 million EU and State funding | Announced December 2024; production planned end 2026 |

| InoBat Battery Gigafactory — Valladolid | InoBat Battery (Chinese-Slovakian JV) + Spanish Consortium | 712 million, including €54 million State grant | Confirmed Sept 2025; operations planned 2028 |

Summary Insight: Spain’s bold statecraft combines a robust domestic policy architecture—anchored in EU frameworks and regional execution—with diplomatic activism that positions the country as an open and reliable partner for green-industrial cooperation. This multifaceted approach enhances Spain’s credibility as a stable, rules-based investment destination while advancing its goal of strategic autonomy through partnership.

🇭🇺 Hungary — Industrial Policy, Narrative Leadership, and Geopolitical Balancing

Context & Drivers

Strategic vision and policy consistency

Under the leadership of Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán, the longest-serving national leader in the EU currently in office, Hungary has committed to electromobility as a cornerstone of its industrial policy. Since 2022 the government has taken an active role in shaping industrial direction – focused on positioning Hungary to become Europe’s leading battery manufacturing hub.

Launched in 2022, Hungary’s National Battery Industry Strategy 2030 identifies battery manufacturing as the country’s “next economic growth engine.” It aligns with EU industrial goals under the Green Deal Industrial Plan and Net Zero Industry Act while emphasising “economic sovereignty” and foreign-investment attraction as national priorities.

Government messaging links this drive to Hungary’s energy-security goals—reducing fossil dependency, modernising manufacturing, and securing export competitiveness—while retaining openness to both Western and Eastern investment partners, including China and South Korea.

As a result, battery production in Hungary has exploded in just a few years. While it was practically non-existent in 2017, by 2023 Hungarian capacity accounted for a quarter of the European battery market.

Firm political support for Chinese ODI

In navigating intensifying US-China competition and the US Government pressuring its allies to choose between the two, the Hungarian Government has responded that ‘decoupling’ from China was a red line, given the benefits Hungary was deriving from being the top recipient of Chinese investment in Europe.

Speaking at the new BYD electric bus plant launch in June 2025, Hungarian Foreign Minister Péter Szijjártó, called this a huge achievement. Specifically, he stated that “in 10 years, the Hungarian government has provided support for 64 major Chinese investments. These Chinese investments represent a total investment of 5,500 billion HUF (13.79 billion EUR) here in Hungary, creating 30,000 new jobs.”

Minister Szijjártó has recently affirmed that Hungary intends to remain the number European destination for Chinese investments. He explained that these Chinese investments “have brought Hungary the most advanced technology and reliable jobs in large numbers. Without all these investments, the Hungarian economy and Hungary would have been poorer.”

“Hungary is proof that Europe can only respond effectively to the great technological revolution taking place in the world if it cooperates closely with China. Hungary is proof that Europe can only come out of the great global automotive transformation if it does not limit the cooperation of European companies with Chinese companies,” Minister Szijjártó said.

Statecraft Tools

| Instrument / Tool | Description |

|---|---|

| Strategic Industrial Policy Framework | The National Battery Industry Strategy 2030 (adopted 2021) sets the objective of making Hungary Europe’s top battery producer by 2030. It establishes a National Battery Council chaired by the Minister of Economy and defines policies for workforce training, local supply-chain development, and industrial land allocation. |

| Investment Promotion and Incentives | The Hungarian Investment Promotion Agency (HIPA) coordinates tailored incentive packages—tax reliefs, infrastructure grants, and expedited licensing—for large-scale clean-technology investments. Projects above €50 million are classified as “priority national economic investments” and receive fast-tracked approval. |

| Regional Industrial Development and Zoning | Industrial parks in Debrecen, Komárom, and Iváncsa have been designated as Battery Industry Zones. Regional governments provide land, utilities, and workforce-training programs in coordination with vocational institutes and universities. |

| Green Energy and Infrastructure Support | Through the Energy Strategy 2030 and RePower Hungary plan, the government supports renewable-energy projects and grid modernisation to meet the needs of large industrial users like CATL and SK On. |

| Public–Private R&D and Education Programmes | The government funds research partnerships between the University of Debrecen, Eötvös Loránd University, and foreign manufacturers to create battery-technology and materials-science curricula, supported by the Neumann Technology Program (2024). |

| Transparent but Strategic Investment Screening | Hungary implements EU FDI screening regulations but with a pragmatic approach prioritising investment facilitation. The Ministry of Economic Development oversees approvals, maintaining transparency while encouraging industrial partnerships with trusted investors. |

| Diplomatic Activism and Partnership with China | Hungary is a BRI partner country and its leadership has cultivated strong bilateral ties with China as part of its “Eastern Opening” policy. In May 2024, Prime Minister Orbán met President Xi Jinping in Budapest, signing cooperation agreements on electric mobility, green manufacturing, and finance. Chinese investments by CATL, EVE Energy, and Sunwoda are publicly celebrated as “mutually beneficial partnerships” contributing to European decarbonisation. |

Perception by Chinese Companies

It is reported Hungary’s attractiveness to listed Chinese clean-tech firms is due to:

- Hungary was the first European country to sign a BRI cooperation document with China.

- Hungary is located in the centre of Europe and is an important transportation hub in Europe.

- Automobiles and auto parts are pillar industries in Hungary. More than 14 of the world’s top 20 automakers have established complete vehicle manufacturing plants and auto parts production bases in Hungary.

- Finally, the Hungarian government provides relatively preferential policies and a favorable business environment for Chinese companies.

Outcomes & Results

Hungary became the leading destination for Chinese ODI in Europe for the second consecutive year in 2024, accounting for 31% of China’s total investment in the EU and the UK, far exceeding Germany, France, and the UK (20% combined). 62% of Chinese EV-related greenfield FDI in Europe went to Hungary. Hungary currently hosts four of China’s top ten projects in Europe, including BYD’s passenger car plant in Szeged, its European headquarters and R&D centre, and CATL’s battery production base in Debrecen.

Table: Announced and ongoing EV value chain projects in Hungary as at October 2025

| Name / Location | Chinese partner | Investment (€) | Status (2025) |

|---|---|---|---|

| CATL 100 GWh Battery Gigafactory — Debrecen | CATL (China) | 7.34bn | Hungary’s largest FDI project ever. Announced 2022; Construction under way; first phase 2026 |

| EVE battery cell plant Energy Plant to supply BMW iFactory — Debrecen | EVE Power | 1.4bn | Announced 2023; expected to create over 1,000 jobs; currently in commissioning phase |

| Sunwoda Battery Factory — Nyíregyháza | Sunwoda | 1.43bn | Expected to create over 2500 direct jobs and over 470 indirect jobs; European Commission approved in August 2025 €264 million in Hungarian state aid |

| BYD EV Manufacturing Plant — Szeged | BYD Auto | 1.4bn | Announced Dec 2023; construction delayed to 2026 |

| BYD electric bus manufacturing plant — Komárom | BYD Auto | 80.25 million | Announced June 2025; expected to create 620 jobs |

| KunlunChem battery electrolyte factory — Szolnok | KunlunChem | 100 million | Announced March 2025; expected to create 120 jobs |

| Huayou Cobalt cathode materials factory – Ács | Huayou Cobalt | 1.3 billion | Expected to create 900 jobs; Environmental permit submitted March 2024 |

Together, these projects would make Hungary Europe’s second-largest EV battery manufacturer after Germany and one of the world’s leading producers based on current investment announcements.

Summary Insight: Hungary’s state-led industrial model combines policy continuity, clear strategic objectives, and active diplomatic engagement with China to anchor its position as Europe’s battery capital. The integration of industrial zoning, education reform, and green-energy infrastructure—underpinned by a predictable investment environment—has enabled Hungary to attract over €16 billion in announced battery and EV projects since 2020, reinforcing its central role in the European clean-tech value chain.

🇸🇦 Saudi Arabia — Vision 2030 and the Strategic Localisation of Renewable Energy

Context & Drivers

Leadership and Vision 2030

Under the leadership of Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, Saudi Arabia has undertaken one of the most ambitious policy reforms in the world. Vision 2030, launched in 2016, is transforming the Kingdom’s economic landscape – diversifying from an oil-dependent economy into a global hub for advanced industry, clean energy, logistics, and technology.

It seeks to expand the non-oil economy, targeting increasing the share of non-oil exports in non-oil GDP from 18.7% to 50% by 2030.

While the country maintains its position as the world’s largest swing oil exporter, a recent S&P Global study found that Saudi government’s efforts to develop the non-oil economy has reduced related economic, fiscal, and external volatility and is yielding tangible results, and estimated non-oil activity to contribute about 57% to total GDP in 2025.

Vision 2030 is implemented through an integrated framework of national strategies—notably the National Industrial Strategy (NIS), Saudi Green Initiative (SGI), and National Renewable Energy Program (NREP)—coordinated by the Council of Economic and Development Affairs (CEDA). These initiatives align industrial diversification with climate ambition, targeting clean energy as both an economic and security imperative.

Statecraft Tools

| Instrument / Tool | Description |

|---|---|

| Vision 2030 and National Industrial Strategy (NIS) | Launched October 2022 by the Ministry of Industry and Mineral Resources, the NIS implements Vision 2030’s industrial pillar and targets a tripling of industrial GDP contribution by 2030. It identifies 12 priority sectors – including renewables, hydrogen, EVs, advanced materials, and mining – and seeks to attract SAR 1.4 trillion (≈ US$ 370 bn) in cumulative industrial investment. |

| Public Investment Fund (PIF) | The PIF, with ≈ US$ 913 bn AUM (2024), is Saudi Arabia’s central vehicle for economic diversification. It finances flagship Vision 2030 projects—including NEOM, Qiddiya, and Red Sea Global—and invests in clean-tech ventures such as Ceer Motors (EVs), ACWA Power (renewables and hydrogen), and Lucid Motors KSA. Its Green Finance Framework (2023) directs capital toward renewable-energy manufacturing and hydrogen value chains. |

| Special Economic Zones (SEZs) and Industrial Clusters | The Economic Cities and Special Zones Authority (ECZA) established four new SEZs in 2023 – including King Abdullah Economic City, Ras Al-Khair, Jazan, and NEOM Oxagon. These zones allow 100 % foreign ownership, 5–20-year tax holidays, and streamlined customs, focusing on green-manufacturing exports (solar modules, EVs, hydrogen equipment). |

| Renewable Energy and Hydrogen Strategies | The Saudi Green Initiative (SGI) and National Hydrogen Strategy (2024) target 50 % clean-energy generation by 2030 and production of 4 million tpa of clean hydrogen by 2035. The National Renewable Energy Program (NREP)—managed by the Ministry of Energy—aims for 130 GW renewable capacity by 2030, cutting domestic oil use in power generation. |

| Industrial Development Fund (SIDF) and Saudi EXIM Bank | The SIDF Transformation 2025 program provides concessional loans, guarantees, and export finance for industrial projects. In 2023, SIDF approved SAR 28 bn (≈ US$ 7.5 bn) in financing, much of it for renewables and manufacturing. The Saudi EXIM Bank supports exports of locally produced solar and industrial components. |

| Human Capability Development Program (HCDP) | One of Vision 2030’s 13 core programs, the HCDP expands STEM education and technical training, builds industry-university partnerships, and aims to upskill 100 000+ citizens by 2025. Initiatives include the Green Skills Academy and NEOM Energy and Manufacturing Training Institute |

| Investment Law (2023) | Enacted June 2023 by the Ministry of Investment (MISA), the law simplifies licensing, guarantees equal treatment for foreign investors, and strengthens IP protection. The new Saudi Investment Marketing Authority (SIMA) serves as a “one-stop shop” for investor onboarding and after-care. |

| Diplomatic Activism and China Partnership | Saudi Arabia has deepened its Comprehensive Strategic Partnership with China, aligning Vision 2030 with the Belt and Road Initiative. State visits in Riyadh (Dec 2022), Beijing (Dec 2023), and Hangzhou (May 2024) produced deals worth > US$ 25 bn in solar, battery, and EV manufacturing. Key MoUs involve LONGi, TCL Zhonghuan, Jinko Solar, GCL Technology, and CATL. |

Outcomes & Results

China is already Saudi Arabia’s top trading partner, with bilateral trade topping $US107.5 billion in 2024. Nearly a quarter of the Kingdom’s crude exports — 24.3% — went to China in early 2025.

Yet the relationship is no longer only about hydrocarbons. Chinese ODI in the Kingdom rose 28.8% to $8.2 billion in 2024, while inflows more than doubled to $US2.3 billion. Driven by Vision 2030, investments now span manufacturing, finance, construction and health care.

Table: Announced green energy and manufacturing projects Oct 2024 – Sep 2025

| Project | Company / Partners | Investment (US$ bn) | Status / Timeline |

|---|---|---|---|

| 20 GW Ingot and Wafer Factory | TCL Zhonghuan (China), PIF, Vision Industries | Undisclosed | Announced July 2024 |

| 10 GW Solar Cell & Module Plant | Jinko Solar (China), PIF | $1 billion | Announced July 2024 |

| Solefiori – 6 GW HJT Module Factory | Solefiori (China) + MODON (Industrial Property Authority) | Undisclosed | Announced June 2025 |

| 1 GW Al Masa’a solar plant + 400 MW Al Henakiyah solar plant | France’s EDF Renewables (France) + SPIC Huanghe Hydropower Development Co (China) | $850 million | December 2024 |

| 2 GW Al Sadawi solar project | Masdar (UAE) + GD Power (China) and Kepco (South Korea) | $1.1 billion from eight regional and international banks | August 2025 |

Summary Insight: Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030 represents one of the most comprehensive national efforts anywhere to translate political vision into industrial transformation. Anchored in clear targets for economic diversification, renewable-energy expansion, and technological localisation, the Kingdom has moved from planning to implementation—using state-backed finance, regulatory reform, and international partnership as instruments of green-industrial statecraft.

Within the wider MENA transformation, Saudi Arabia functions as the region’s industrial anchor: a platform that links Chinese manufacturing capacity and capital with Gulf energy resources and European market demand. Its Public Investment Fund (PIF) and National Industrial Strategy are turning the ambition of Vision 2030 into bankable joint ventures across solar, hydrogen, and EV manufacturing. In doing so, Saudi Arabia not only advances its own diversification agenda but also positions itself at the centre of an emerging Asia–MENA–Europe “Green Silk Road”, where industrial partnership replaces raw-resource dependency as the foundation of regional power and prosperity.

SECTION 4:

The Australian context

Chinese ODI in Australia at historic low

In sharp contrast to the trends detailed above, Chinese investment in Australia has collapsed to historically low levels, falling by 85% since 2018 (see Figure 2). Chinese ODI now makes up only 1.5% of total ODI into Australia, compared to over 10% in 2018, and down from the already extremely low 1.87% in 2023 (see Figure 3). China is the third largest outbound investor–but now ranks 13th in Australia, having slipped from 8th in 2021.

Despite a 41% year-on-year increase, 2024 recorded the third-lowest value and number of transactions since 2006, at just US$882 million—a fraction of the peaks above US$16 billion in 2008 and US$11 billion in 2016 (see Figure 2). No new investment proposals by Chinese state-owned companies have passed FIRB since 2016. In 2024, private firms led most projects, but capital contributions from state-owned companies still represented 71% of the total amount invested, primarily in mining.

Figure 2: Collapse of Chinese ODI into Australia since 2018 underscores lost opportunity under security-driven screening

Source: KPMG & University of Sydney, Demystifying Chinese Investment in Australia 2025

Figure 3

Sources: DFAT; KPMG and University of Sydney

Although the official government line is that foreign investment review framework is country-agnostic, many Chinese investors have reported that investing in “Australia is too hard and not stable”. As in the United States, political dynamics have influenced the behaviour of Chinese investors in Australia, limiting the appetite for new investments, and much of the recent investment, although formally linked to Australian companies, involves mining assets located outside the country.

How did we get here?

Treasury’s Australia’s Foreign Investment Policy states that “the Government reviews foreign investment proposals on a risk-based, case-by-case basis to ensure they are not contrary to the national interest”. It is clear from this very language that it has a defensive orientation.

The policy also states that investments “critical infrastructure, critical minerals, critical technology, and those in proximity to sensitive Australian Government facilities or involving sensitive data will face greater scrutiny to protect the national interest.” Renewable energy generation and transmission are seen as critical infrastructure, with the potential risks framed as involving intersection with the electricity grid. Yet, there is little specific investigation of the nature and magnitude of potential risks and vulnerabilities, and there is no history of such risks materialising in the existing portfolio of energy and transmission assets with Chinese company stakes.

A 2024 study of Chinese companies in the Swedish wind energy sector, which control 10.4% of Sweden’s installed wind power capacity, found that the risk of ownership being used to cause electricity supply cuts and price manipulation was deemed low due to the limited market impact and high costs such actions would incur for Chinese interests.”

Table X: Existing and announced renewable energy and transmission projects in Australia

| Project / Asset | Investment (US$) | Chinese Company | Status / Additional Info |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kiewa Valley 500MW/1,000MWh battery energy storage system (BESS) | $300 million | Trina Solar | Approved September 2025 after fast-track via Victorian Government’s Development Facilitation Program |

| Killawarra 400 MW solar and 400 MW BESS hybrid project | 455.5 million | Trina Solar | Would be the largest solar farm in Western Australia; development application under review |

| Bashan 200-400MWh wind-plus-storage project | ? | Goldwind | Application submitted Feb 2025 for environmental and planning approval |

| Musselroe 168 MW Wind Farm (Tasmania) | Wind power | Shenhua Clean Energy owns 75 % | Commissioned 2013; operated via joint ownership with Hydro Tasmania (25 %) |

| Pacific Blue (formerly Pacific Hydro) ~ 660 MW | Renewables portfolio (wind, solar, hydro) | State Power Investment Corporation (China) | Chinese-owned generation & retail firm operating multiple renewable sites in Australia |

| Jemena (Energy infrastructure / transmission & distribution) | Electricity networks / infrastructure | State Grid Corporation of China owns 60 % | Jemena owns and operates transmission / distribution networks in NSW, Victoria, Queensland & other eastern states. |

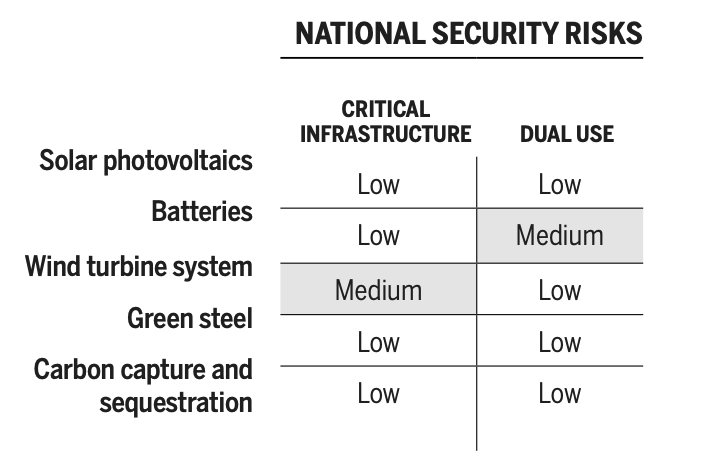

While some risk concerns are legitimate, they may be overstated in clean-tech sectors due to interdependence and commercial constraints. A 2022 study published in Science, for example, assessed national security risks across five key low-carbon technologies and found that the risks associated with integration with China were mostly low to medium (see Figure 4 below).

Figure 4

Source: Risks of decoupling from China on low-carbon technologies, September 2022

This approach, perceived as discriminatory by many Chinese companies, continues to inhibit the restoration of mutual trust, which limits cooperation between the two countries bilaterally and regionally to solve global challenges, such as climate change and energy transition. Australia’s AUKUS commitment and the cancellation of the Darwin port lease are perceived as antagonistic, further reinforcing the perception of Australia’s “deputy Sheriff” role in the region. Meanwhile, China is pursuing its own supply chain diversification strategy including reducing dependence on Australian iron ore – for example, its investment in the Simandou high-grade iron ore mine in Guinea, dubbed the “Pilbara killer”.

FMIA bound up with US alliance

It is noteworthy that while other countries have formulated green industrial strategies as enablers of sovereignty, Australia’s FMIA was designed in close collaboration with the US Biden Government to primarily serve the objective of “diversifying clean energy and critical minerals supply chains”. In fact, its genesis can be seen in the announcement in 2023 of the Climate, Critical Minerals and Clean Energy Transformation Compact, “establishing climate and clean energy as a central pillar of the Australia-United States Alliance”.

Despite Trump’s withdrawal of the US from the Paris Agreement and of support for renewables policies such as the IRA, Albanese has maintained FMIA’s alignment with the US alliance. In a September 2025 speech addressing US investors in New York, he declared unequivocally that FMIA “is a ready-made opportunity for investment from America”.

This choice effectively shackles Australia’s industrial policy to an unstable alliance, deepening our dependency on the US through a narrow security lens, while limiting our ability to collaborate with the world’s largest clean tech leader –China’s total investment in energy transition technologies last year was greater than the combined investment of the US, EU and UK. It is difficult to see how the government’s approach is in Australia’s national interest, noting Trump’s anti-renewables stance and MAGA agenda, China’s clean tech leadership, and the fact that we now live in a multipolar world.

“Prioritising security or geopolitical considerations always comes at the cost of efficiency. This trade-off will not disappear.”

– Javier Borràs Arumí, Barcelona Centre for International Affairs

If FMIA continues to exclude the world’s clean-tech leader, Australia risks marginalising itself in the global green economy

The Australian approach outlined above has turned away the very firms that lead the world in solar, battery, hydrogen and critical-minerals technology—precisely the sectors the FMIA and Net Zero Plan identify as priority industries.

This is not only resulting in missed investment opportunities, but also deters broader spillover benefits that are critical for developing a domestic knowledge base and innovation ecosystem capable of participating in global clean-tech and emerging next-gen-tech value chains. Just at a moment when Australia’s sluggish economy desperately needs these. Since COVID-19, Australians have experienced the sharpest decline in living standards compared with OECD economies.Australia continues to experience record low productivity growth, rising socio-economic inequality, and coupled with increasingly frequent and severe extreme weather events and geopolitical conflicts.

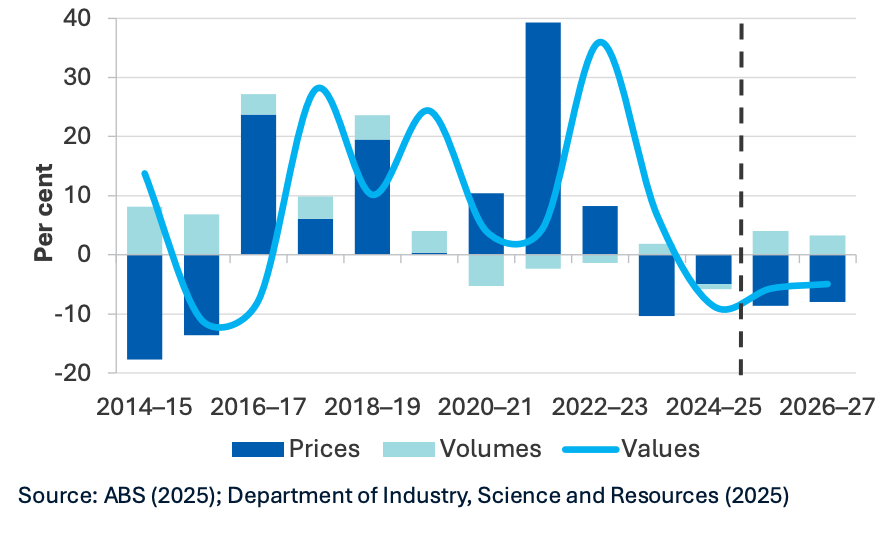

Australia’s economic complexity ranking—one of the lowest among developed nations (105 of 145 countries) – has been falling over the last decade, due to a lack of diversification of exports. A reliance on mining has left the nation vulnerable to global market shifts and geopolitical tensions. The harsh reality is that the mining industry, once Australia’s economic growth engine, has been in recession for five years, and in trouble (see figure X below). Australia’s resource and energy export earnings are forecast to decline by 5% to $369 billion in 2025–26, down from $385 billion in 2024–25. A further fall to $354 billion is forecast in 2026–27.

Figure X: Annual growth in Australia’s resources and energy export values, contributions from prices and volumes

Australia’s largest export – iron ore – is under threat due to China’s pivot to decarbonising steel production, and new supplies coming on, especially Simandou in West Africa, and the gradual return of Brazil, as China is continuing its long-standing approach of supply diversification.

The potential for Australia to become a value-adding producer of green iron, as opposed to simply digging and shipping raw iron ore, has been garnering much attention, and is Australia’s #1 trade opportunity in a decarbonised global economy. However, the capital-intensive nature of this challenge is huge. According to a report by the Superpower Institute, there are three main obstacles to green iron production in Australia: lack of financial support for early investors, underdeveloped infrastructure and an absence of a global carbon price, making green production less competitive.

Despite the establishment of a China-Australia Steel Decarbonisation Dialogue during Albanese’s July trip to China, CEF understands that genuine interest on the Chinese side remains lukewarm, given the cost premium and fragile state of the bilateral relationship.

Plainly, the global clean industrial race is a race to attract capital, the best technology and knowledge, with no shortage of countries, as detailed above, competing for these in order to obtain a slice of the green industrial value chain pie.

While Canberra debates risk, the critical investment, scale, technology and knowhow required to achieve the nation’s energy transition and economic resilience imperative, go to other nations, strengthening their competitiveness and leaving Australia further behind.

The solution: Strategic pragmatism – collaborate to get into the race

In the face of intersecting and pressing national problems, it is urgent that Australian leaders find the foresight, courage and resolve to let go of legacy security frameworks and free up policy space to urgently grasp the emerging global trends and dynamics and deploy mission-led “green energy statecraft” that sees strategic co-investment and partnership with China, the global leader of clean tech supply chains, as a strategic priority, not a threat. The security and prosperity of present and future generations of Australians depend on it.

SECTION 5:

China’s Foreign Direct Investment In Cleantech Manufacturing & Infrastructure Oct 2024-Sept 2025

Table: Confirmed cleantech manufacturing projects announced Oct 2024 – Sep 2025

| Country | Project Type, Size & Description | Investment ($US) | Companies | Green industrial policy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ASEAN | ||||

| Malaysia | PV inverters / equipment – Ningbo Deye solar equipment manufacturing base. | 150 million | Ningbo Deye | Dec 2024 – reported |

| Founder Group signs MoU to explore, identify, assess and undertake renewable energy projects across Malaysia and ASEAN | 220 million | GCL Technology | Announced June 2025 | |

| Indonesia | Integrated battery chain (mining → cells → recycling) – CATL Indonesia Battery Integration; initial 6.9 GWh capacity; 8,000 direct + 35,000 indirect jobs. | 6 billion | CATL (+ local partners) | Jul 2025 – construction began |

| Integrated 1GW solar panel factory; 640 local jobs created | 90.5 million | Trina Mas Agra Indonesia | Opened June 2025 | |

| 1.4 GW solar cell and module factory (Deltamas) | ? | LONGi Green Energy (China) + Pertamina New & Renewable Energy (Indonesia) | JV launched June 2025 | |

| Europe | ||||

| France | Solar modules (3 GW) – DAS Solar assembly plant (Mandeure) + cells (5 GW) plant; R&D and recycling partnership (SUEZ; IPVF); assembly by end-2025; cells by 2026 | 784 million | DAS Solar | France 2030 |

| Battery components (CAM/PCAM) (Dunkirk)Dec 2024 – JVs announced | N/A | Orano + XTC New Energy joint venture | ||

| EV batteries (10 GWh) (Douai) to supply Renault’ | N/A | Envision AESC | Jun 2025 – production start celebrated | |

| Hungary | Battery electrolyte plant to supply CATL/EVE; announced Mar 2025 | 108 million | KunlunChem | EU ICE ban from 2035 Hungarian National Battery Industry Strategy 2030 |

| E-bus & e-truck manufacturing expansion (Komárom) + European HQ & new R&D in Budapest; announced June 2025 | 86.7 million | BYD | ||

| Portugal | Energy-storage batteries (15 GWh) – CALB gigafactory (Sines); 1,800 jobs; announced Feb 2025; full operation by 2028 | 2.1 billion | CALB | EU ICE ban from 2035 Portugal 2030 |

| Spain | 50GWh EV battery gigafactory (Zaragoza); announced Dec 2024; Oct 2025 – site mobilisation; production 2028 | 4.43 billion, including 324 million state grant | CATL + Stellantis (50:50 joint venture) | EU ICE ban from 2035 National Integrated Energy and Climate Plan 2023-2030 Strategic Projects for Economic Recovery and Transformation (PERTES) |